belief

Why Don’t You Believe?

I have proof that god exists?

How can you deny holy texts like Iliad and Odyssey Theogony. Look around you, the evidence is all over. Look at the war in Iraq – proof of Ares. The high divorce rate shows Hera isnt happy. Look at the sea, evidence of Poseidon. Look at the exquisite wines and wild parties going on, thats the work of Dionysus. Cant you see great musicians are products of Apollo and great minds of Athena. Why dont you people believe. Are you afraid Zeus will strike you down with lightning. Are you too proud to repent. Why dont you accept the fact that there are beings bigger than you out there. You know what, it is your souls that will be banished to the underworld and befriend Hades.

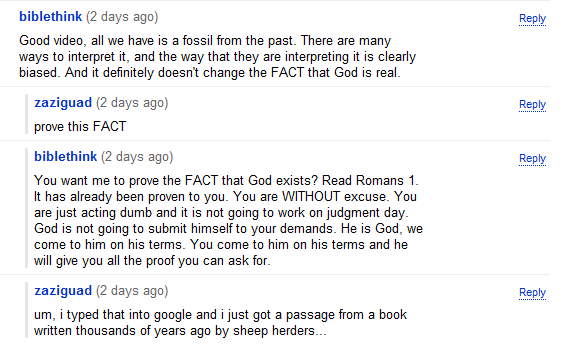

God Exists! It’s Fact!

Well, I’m sold. God has been proven. Though this does leave one question; if you know god exists (as a fact), then why do you need faith? I thought belief in god was all about faith and not needing proof. Hmm.

Researchers find brain differences between believers and non-believers

Researchers find brain differences between believers and non-believers

In two studies led by Assistant Psychology Professor Michael Inzlicht, participants performed a Stroop task – a well-known test of cognitive control – while hooked up to electrodes that measured their brain activity.

Compared to non-believers, the religious participants showed significantly less activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a portion of the brain that helps modify behavior by signaling when attention and control are needed, usually as a result of some anxiety-producing event like making a mistake. The stronger their religious zeal and the more they believed in God, the less their ACC fired in response to their own errors, and the fewer errors they made.

“You could think of this part of the brain like a cortical alarm bell that rings when an individual has just made a mistake or experiences uncertainty,” says lead author Inzlicht, who teaches and conducts research at the University of Toronto Scarborough. “We found that religious people or even people who simply believe in the existence of God show significantly less brain activity in relation to their own errors. They’re much less anxious and feel less stressed when they have made an error.”

These correlations remained strong even after controlling for personality and cognitive ability, says Inzlicht, who also found that religious participants made fewer errors on the Stroop task than their non-believing counterparts.

Their findings show religious belief has a calming effect on its devotees, which makes them less likely to feel anxious about making errors or facing the unknown. But Inzlicht cautions that anxiety is a “double-edged sword” which is at times necessary and helpful.

“Obviously, anxiety can be negative because if you have too much, you’re paralyzed with fear,” he says. “However, it also serves a very useful function in that it alerts us when we’re making mistakes. If you don’t experience anxiety when you make an error, what impetus do you have to change or improve your behaviour so you don’t make the same mistakes again and again?”

The study is appearing online now in Psychological Science.

Source: University of Toronto

Atheist Revival in Arkansas

Atheist Revival in Arkansas

Hard to say what was more remarkable about the resolution that was read into the record and referred to committee Wednesday by a member of the 87th Arkansas General Assembly.

The resolution itself:Â HJR 1009: AMENDING THE ARKANSAS CONSTITUTION TO REPEAL THE PROHIBITION AGAINST AN ATHEIST HOLDING ANY OFFICE IN THE CIVIL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE OF ARKANSAS OR TESTIFYING AS A WITNESS IN ANY COURT.

Or the fact that it was submitted by the Green Party’s highest-ranking elected official in America, state Rep. Richard Carroll of North Little Rock, who was elected in November winning more than 80 percent of the vote in his district.

Arkansas is one of half a dozen states that still exclude non-believers from public office. Article 19 Section 1 of the 1874 Arkansas Constitution states that “No person who denies the being of a God shall hold any office in the civil departments of this State, nor be competent to testify as a witness in any court.”

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled all such state provisions unconstitutional and unenforceable in a 1961 ruling in a Maryland case: “We repeat and again reaffirm that neither a State nor the Federal Government can constitutionally force a person ‘to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion.'”

Carroll is merely trying to do some symbolic constitutional housecleaning, but it won’t be easy.

In 2005, state Rep. Buddy Blair filed a resolution to affirm Arkansas’ support for the separation of church and state. The resolution lost 39-44 in the House.

And last month, Rep. Lindsley Smith offered a resolution to declare Jan. 29 at Thomas Paine Day in Arkansas.

“I consider myself a very religious person,” Smith told the committee considering her bill to designate Jan. 29 as Thomas Paine Day in Arkansas. Paine, the colonial patriot who wrote “Common Sense,” a pamphlet that built support for the American Revolution. Paine also was a Deist who believed in God but not religion.

The proposal died in committee, even after Smith assured her colleagues that she was not an atheist. Which they would have known if they’d read the state constitution.

Meanwhile, in a related story, the Arkansas House passed a bill Wednesday allowing people to bring their guns to church.

“Due to many shootings that have happened in our churches across our nation, it is time we changed our concealed handgun law to allow law-abiding citizens of the state of Arkansas the right to defend themselves and others should a situation happen in one of our churches,” said state Rep. Beverly Pyle.

The bill doesn’t say whether atheists can bring guns to church.

God Made My Plane Crash – THANK GOD!

God saved my life after he decided to make my plane crash in the Hudson river! I wasn’t a believer before, but since I survived (not because I had a good pilot), I praise and love God! Glory be to God!

Hudson River jet crash passenger: ‘Believe in angels’

From the bitter cold and ice enveloping New York City, they were headed south on US Airways Flight 1549, south to Charlotte, N.C. Some were making the two-hour flight on business, some for the pleasure of a golf trip where the day’s high would not be 15 degrees. One 85-year-old woman was flying the 660 miles for her great-grandson’s birthday.

A number of the passengers weren’t supposed to be on Flight 1549 at all. Their earlier flights had been canceled because of the weather.

So these 155 souls — passengers, pilots and flight crew — took off from LaGuardia Airport at 3:24 p.m. In the next six minutes, Flight 1549 crash-landed into the Hudson.

“There was a sudden jerk, it just felt like turbulence,” said Bill Zuhoski, 23, of Cutchogue, who was in seat 23A, well back of the wing on the plane’s left side. “No one thought anything of it until we started to go down.”

Jeff Kolodjay of Norwalk, Conn., was in seat 22A. He said he knew immediately that something was terribly wrong.

“I heard a loud explosion from the left side of the plane,” Kolodjay said. The smell of gas was strong.

Zuhoski said he “heard a stewardess looking for a fire extinguisher.”

Dave Sanderson, 47, a father of four headed home to Charlotte after one of his frequent business trips to the city, was sitting several rows forward of both Zuhoski and Kolodjay, and his experience was similar to Kolodjay’s.

“I heard an explosion and saw some flames coming from the left wing,” said Sanderson, who works for Oracle.

Kolodjay, going to Myrtle Beach, S.C., with his father and four other men on a golf outing, also spotted the telltale orange of flames.

“I could see fire, kind of, passing by my window,” he said.

Three minutes after takeoff, with Flight 1549 about five miles north of the airport, the pilot reported multiple bird strikes, according to the Federal Aviation Administration.

The pilot declared an emergency and hoped to return and land at LaGuardia. But the jet’s two engines were losing thrust, and air-traffic controllers said no runway was open.

At 3:30 p.m., controllers spotted the jet over the Hudson River, south of the George Washington Bridge. Between 300 and 400 feet, it disappeared from the radar screen.

“Brace for impact!” pilot Chesley Sullenberger commanded the passengers.

“Everybody started saying prayers,” Kolodjay said. ” ‘Brace for impact’ is not what you want to hear.”

Sanderson described the scene as “controlled chaos,” with everyone “running away from their seats” toward the rear of the aircraft.

“We didn’t know if we would be hitting water or land,” Zuhoski said. “People rushed to the back of the plane.”

The plane hit the water.

Why I Am Not A Christian – Bertrand Russell

Why I Am Not A Christian

As your Chairman has told you, the subject about which I am going to speak to you tonight is “Why I Am Not a Christian.” Perhaps it would be as well, first of all, to try to make out what one means by the word Christian. It is used these days in a very loose sense by a great many people. Some people mean no more by it than a person who attempts to live a good life. In that sense I suppose there would be Christians in all sects and creeds; but I do not think that that is the proper sense of the word, if only because it would imply that all the people who are not Christians — all the Buddhists, Confucians, Mohammedans, and so on — are not trying to live a good life. I do not mean by a Christian any person who tries to live decently according to his lights. I think that you must have a certain amount of definite belief before you have a right to call yourself a Christian. The word does not have quite such a full-blooded meaning now as it had in the times of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas. In those days, if a man said that he was a Christian it was known what he meant. You accepted a whole collection of creeds which were set out with great precision, and every single syllable of those creeds you believed with the whole strength of your convictions.

What Is a Christian?

Nowadays it is not quite that. We have to be a little more vague in our meaning of Christianity. I think, however, that there are two different items which are quite essential to anybody calling himself a Christian. The first is one of a dogmatic nature — namely, that you must believe in God and immortality. If you do not believe in those two things, I do not think that you can properly call yourself a Christian. Then, further than that, as the name implies, you must have some kind of belief about Christ. The Mohammedans, for instance, also believe in God and in immortality, and yet they would not call themselves Christians. I think you must have at the very lowest the belief that Christ was, if not divine, at least the best and wisest of men. If you are not going to believe that much about Christ, I do not think you have any right to call yourself a Christian. Of course, there is another sense, which you find in Whitaker’s Almanack and in geography books, where the population of the world is said to be divided into Christians, Mohammedans, Buddhists, fetish worshipers, and so on; and in that sense we are all Christians. The geography books count us all in, but that is a purely geographical sense, which I suppose we can ignore.Therefore I take it that when I tell you why I am not a Christian I have to tell you two different things: first, why I do not believe in God and in immortality; and, secondly, why I do not think that Christ was the best and wisest of men, although I grant him a very high degree of moral goodness.

But for the successful efforts of unbelievers in the past, I could not take so elastic a definition of Christianity as that. As I said before, in olden days it had a much more full-blooded sense. For instance, it included he belief in hell. Belief in eternal hell-fire was an essential item of Christian belief until pretty recent times. In this country, as you know, it ceased to be an essential item because of a decision of the Privy Council, and from that decision the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York dissented; but in this country our religion is settled by Act of Parliament, and therefore the Privy Council was able to override their Graces and hell was no longer necessary to a Christian. Consequently I shall not insist that a Christian must believe in hell.

Intelligent people ‘less likely to believe in God’

I’m not surprised in the least.

Intelligent people ‘less likely to believe in God’

Professor Richard Lynn, emeritus professor of psychology at Ulster University, said many more members of the “intellectual elite” considered themselves atheists than the national average.

A decline in religious observance over the last century was directly linked to a rise in average intelligence, he claimed.

But the conclusions – in a paper for the academic journal Intelligence – have been branded “simplistic” by critics.

Professor Lynn, who has provoked controversy in the past with research linking intelligence to race and sex, said university academics were less likely to believe in God than almost anyone else.

A survey of Royal Society fellows found that only 3.3 per cent believed in God – at a time when 68.5 per cent of the general UK population described themselves as believers.

A separate poll in the 90s found only seven per cent of members of the American National Academy of Sciences believed in God.

Professor Lynn said most primary school children believed in God, but as they entered adolescence – and their intelligence increased – many started to have doubts.

He told Times Higher Education magazine: “Why should fewer academics believe in God than the general population? I believe it is simply a matter of the IQ. Academics have higher IQs than the general population. Several Gallup poll studies of the general population have shown that those with higher IQs tend not to believe in God.”

He said religious belief had declined across 137 developed nations in the 20th century at the same time as people became more intelligent.

But Professor Gordon Lynch, director of the Centre for Religion and Contemporary Society at Birkbeck College, London, said it failed to take account of a complex range of social, economic and historical factors.

“Linking religious belief and intelligence in this way could reflect a dangerous trend, developing a simplistic characterisation of religion as primitive, which – while we are trying to deal with very complex issues of religious and cultural pluralism – is perhaps not the most helpful response,” he said.

Dr Alistair McFadyen, senior lecturer in Christian theology at Leeds University, said the conclusion had “a slight tinge of Western cultural imperialism as well as an anti-religious sentiment”.

Dr David Hardman, principal lecturer in learning development at London Metropolitan University, said: “It is very difficult to conduct true experiments that would explicate a causal relationship between IQ and religious belief. Nonetheless, there is evidence from other domains that higher levels of intelligence are associated with a greater ability – or perhaps willingness – to question and overturn strongly felt institutions.”